2021-07-02 11:00:56

2563

100 YEARS OF THE ARMENIAN SCREEN

|

April 16, 2023 marks the centenary of Armenian film industry, which was established one hundred years ago in the Soviet Republic of Armenia, on the basis of one nationalized movie theatre and a miniscule budget of 60 rubles. Less than two years later, the first Armenian film production, the documentary feature Soviet Armenia was released across the USSR, setting course for one of the most multifaceted and complex cinematic legacies in the Near East.

Though comparably modest in scale, the output of Armenian film industry boasts a number of internationally-recognized works whose impact and importance extends far beyond the confines of Armenian culture. Aside from globally-revered masterpieces by the likes of Sergei Paradjanov and Artavazd Pelechian, Armenian films also served as an important early platform for some of the first realistic, anti-colonial depictions of Middle-Eastern nations.

The narratives and issues touched upon by Armenian filmmakers address key problems that have defined the development of human civilization throughout modernity. The relevance of these perspectives is particularly tangible and fresh today, since they address universal subjects, such as global wars, genocide, colonialism, class oppression, cultural identity, gentrification and women's rights, from a peripheral position where Western and Eastern cultural paradigms meet, clash and often interlope.

Intending to both celebrate and critically re-assess this rich heritage, the National Cinema Centre of Armenia has devised an extensive series of programs and restoration projects that aim to introduce the latter to new audiences internationally and present the trajectory of Armenian cinema in the context of global cinematic developments and achievements. |

THE PIONEER OF MODERN "EASTERN" CINEMA:

THREE RESTORED FILMS BY HAMO BEKNAZARYAN

Feted as one of the preeminent Soviet filmmakers during the 1920s-1950s, the leading auteur of early Armenian cinema, Hamo Beknazaryan (1891-1965) has left an outstanding legacy of nearly three dozen feature and documentary films that has few parallels in Soviet film history. With major works shot in Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Russia, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, Beknazaryan was an epitome of cosmopolitan mentality and an ardent believer in cinema as a tool for cultural emancipation.

In 2022, the National Cinema Centre of Armenia embarked on an ambitious project to digitally preserve and disseminate Beknazaryan's complete filmography. The first stage of this initiative consists of three lesser-known works from the director’s mid-career period that reveal Beknazaryan as a multifaceted auteur and showcase his attempts to create a framework for "national" cinema in the context of centralized Soviet film production. Made from the best available source materials held at the National Archive of Armenia, these new digital versions of House on a Volcano (1928), Land of Nairi (1930) and The Daughter (1942) are the first Beknazaryan films to be professionally restored in 4K format. The restorations will receive their international premiere at the 2023 edition of Tout La Mémoire du Monde Film Festival held by the Cinématheque Française.

THE HOUSE ON A VOLCANO

|

After establishing his reputation with a series of highly successful historical dramas, Hamo Beknazaryan undertook his first feature on revolutionary subject matter. Shot on location in the oilfields of Baku, The House on a Volcano addressed this city’s vital role in the entrenchment of the Bolshevik movement in Transcaucasia during the 1900s. The film’s narrative revolves around multiple characters who represent the Armenian and Azerbaijani oil-field labourers and their struggles against the tyranny of capitalist magnates. Buoyed by socialist ideals, the proletariat overcomes inter-ethnic strife to face a common enemy that has put their lives under jeopardy by forcing them into unsafe housing built on gas deposits. Beknazaryan mixed elements of melodrama, thriller and disaster genres to create a gripping picture that delivers its ideological messages through cinematically inventive means. By interweaving the symbolism of expressionist lighting with the kinetic force of the Eisensteinian montage, the director not only consolidated the films byzantine plot into its swift running time, but also managed to crystalize the multiple experimental trajectories of early Soviet cinema into an aesthetically and emotionally rousing spectacle. |

|

|

THE HOUSE ON A VOLCANO, 1928, dir. Hamo Beknazaryan, silent, b/w, 61 min. Production of Armenkino and Azgoskino Studios. New music score by Juliet Merchant, commissioned by Kino Klassika Foundation. |

LAND OF NAIRI

|

Dedicated to the 10th anniversary of Armenia’s sovietisation, Land of Nairi was Beknazaryan's first feature documentary, which presented a vast historical panorama of Armenia’s transition from a Russian colony to a Soviet Republic. Admitting to total indifference towards the documentary format, Beknazaryan approached his subject like a dramatic tale in which the central character is the country itself, which is rendered through poetic, and, at times, surreal lens. Composed entirely of archival footage and staged scenes, this meta-narrative consists of stereotypically broad motifs often borrowed from the director’s own films. |

|

|

LAND OF NAIRI, 1930, dir. Hamo Beknazaryan, silent, b/w, 56 min. Production of Armenkino Studio. New musical score by Vahagn Hayrapetyan, commissioned by Armenian Cultural Association of British Columbia. |

THE DAUGHTER

|

As a 1941 laureate of the ‘coveted’ Stalin prize, Hamo Beknazaryan was among the handful of Soviet filmmakers allowed to direct films under Stalin’s autocratic control of the Soviet film industry known as a period of “malokartinye” (picture drought). Thus, The Daughter became one of the very few narrative films made in Armenia during the 1940s, most of which directly or implicitly served the anti-fascist campaign, or the consolidation of Stalinist policies. While promulgating the expected wartime rhetoric, Beknazaryan primarily focused on the moving drama of two orphaned Russian children who are adapted by an Armenian railway station master and his wife. The archetypal subject provided the director an occasion to explore one of his favoured themes – the entanglement between people of different ethno-cultural backgrounds and their capacity to build connections based on universal values. This deeply humanist perspective is underscored by the film’s metaphorical use of landscape and 'pictorial' compositions, beautifully lensed by Beknazaryan’s frequent collaborator, cinematographer Dmitri Feldman. The distilled visual lyricism of this picture would help to define not only the ‘classicist’ aesthetic of Beknazaryan’s later films, but also of much of Armenian cinema until the mid-1950s. |

|

|

THE DAUGHTER, 1942, dir. Hamo Beknazaryan, b/w, 24 min. Production of Yerevan film studio. |

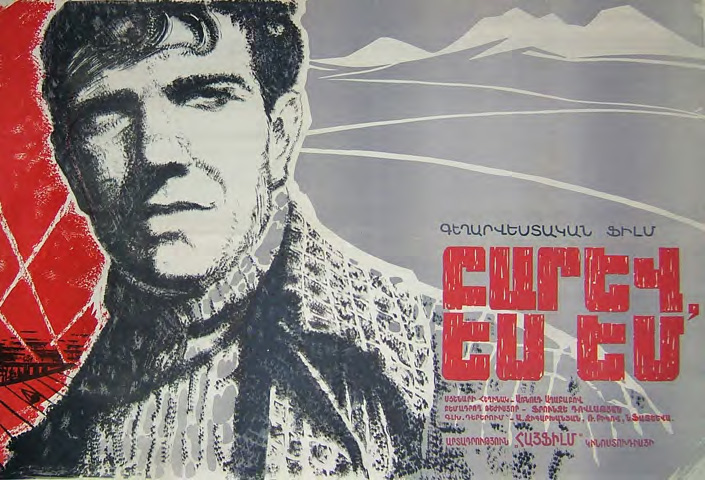

HELLO, IT’S ME:

THE REVIVAL OF A MODERNIST MASTERPIECE

The third feature film and the first made in his home country by director Frunze Dovlatyan (1927-1997), Hello, It’s Me (1965) is a cinematic milestone that acted as a harbinger of the modernist turn in Armenian visual culture. Unabashedly experimental, this sprawling tale of lost love and post-war ennui projected a boldly intellectual vision, which led to its selection for the official competition of the Cannes Film Festival in 1966. A fictionalized biopic of the great Armenian physicist Artem Alikhanyan, the film tells the story of a talented young scientist who looks back at the difficult choices and personal loses he experienced in order to realize a seemingly impossible dream of building an internationally-renowned space-ray research center on Armenia’s highest mountain, Aragats.

Poetically non-linear, Hello, It’s Me is a complex meditation on the clash of cultures and the importance of memory in defining our collective identity. Aided by Albert Yavuryan’s fluid widescreen cinematography and Martin Vardazaryan’s melancholic jazz score, the film captured the anxious spirit of 1960s Soviet culture and touched on highly sensitive political issues pertaining to Armenia’s traumatic past that were only beginning to reemerge from decades-long suppression and silencing. The combination of this critical outlook with surprisingly frank portrayals of sexual desire made the picture wildly popular with audiences across the USSR, and a source of influence for Dovlatyan’s peers. This success was also significantly aided by the exceptional performances of the film’s iconic cast – Armen Djigarkhanyan, Rolan Bykov, Natalya Fateyeva and the beguiling Margarita Terekhova, who was making her screen debut here. The powerfully metaphorical visual style and focus on contemporary issues in Hello, It’s Me broke new ground in local cinema, helping to define Armenia’s own cinematic 'New Wave'. It is an achievement that is going to be celebrated with a new 4k restoration of the film by the National Cinema Centre of Armenia, which will be premiere in the Classics section of the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

LEV ATAMANOV: THE ARMENIAN MAVERICK OF WORLD ANIMATION

|

2023 marks the 85th anniversary of Armenian animation, which was founded by one of the mavericks of the medium, Lev Atamanov (Levon Atamanyan, 1905-1981). Widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in world animation, Atamanov began his career in Moscow, creating one of the very first sound animated features, The Tale of the Little White Bull (1933), before moving to Yerevan, Armenia in 1936. Working with minimal resources, the young director established the animation department of the Haykino (Hayfilm) Studio, which produced its first short film, The Dog and the Cat in 1938. Evidently inspired by Walt Disney’s stylistic vocabulary, Atamanov’s black and white comedy was a bold attempt to create a visually modern rendition of possibly the most famous, eponymously-titled Armenian fairy-tale written by Hovhannes Tumanyan. This allegorical parable of an endless feud between a naive shepherd dog and a sly tailor cat has long become a cornerstone of Armenian cultural mythology. Aided by a sparkling script by another virtuoso of Soviet cinema, Alexander Ptushko, Atamanov’s adaptation helped to popularise Tumanyan’s timeless, cautionary message about human folly not only in Armenia, but across the entire USSR. |

|

The huge success of this sophomore effort promised a very bright future for animation in the country. But the onset of WWII and the stifling of film production in the USSR by Stalin’s oppressive policies meant that Atamanov was able to complete only two more films in Armenia, before returning to Moscow in 1948. His post-war career at Soyuzmultfilm Studio would be a path laden with groundbreaking masterpieces, such as The Golden Antelope (1954) and The Snow Queen (1957), which brought the Armenian director international fame. Today, Atamanov is considered a figurehead in animation’s history, with major auteurs like Hayao Miyazaki citing him as a crucial influence. The three films that the director realised in his historical homeland are some of the most precious treasures in the annals of Armenian cinema, which have not yet received the wider, international exposure that they deserve. To enable the rediscovery of these forgotten gems, the National Cinema Centre of Armenia has undertaken a new 4K restoration of The Dog and the Cat from the original camera negative held in the Gosfilmofond film archive in Moscow. The project will be realised by Riga-based Locomotive Studio and be available for screenings in May 2023. |

|

PIONEERING WOMEN IN ARMENIAN ANIMATION

Armenian animation has had a long and twisted history. After being established in the late 1930s by the great Lev Atamanov, this burgeoning branch of filmmaking was cut short in 1940s by Stalin’s repressive policies. Revived in the 1960s, animation soon became one of the most creative and celebrated facets of Armenian cinema. It was also the only area of filmmaking that provided an entry point for women filmmakers during the Soviet years. Between 1970s and 1990s four important women directors got their start in Armenian animation, significantly influencing the development of the medium and bridging its transition into Armenia’s post-Soviet era.

|

Employing various animation techniques, the work of Gayane Martirosyan, Elvira Avakyan, Lyudmila Sahakyants and Naira Muradyan enriched this art form not only with highly idiosyncratic stylistic sensibilities, but also new thematic concerns that addressed contemporary life, politics and technology. As a result, local animation evolved into a more complex and artistically diverse phenomenon, whose high standing was acknowledged far beyond the borders of Armenia. A number of these films, such as Lyudmila Sahakyants’ The Congregation of Mice (1977) and Gayane Martirosyan’s The Inventor Frog (1982) have become an integral part of Armenia’s popular culture. Gayane Martirosyan and Naira Muradyan were also instrumental in upholding the tradition of artistic animation in Armenia during the first two decades of the 21st century, when the medium faced an existential crisis due to lack of funding. Despite this, the achievements of Armenian women animators have largely been overshadowed by their male peers, with many of their works languishing in obscurity and in dire need of preservation and restoration. |

In 2023, on the occasion of the 85th anniversary of Armenian animation, the National Cinema Centre of Armenia has undertaken a major digitization and restoration project, which will help preserve 12 films by these pioneering women filmmakers and bring them to new audiences worldwide. Sourced from best available 35mm materials held in Armenian and Russian archives, these new 4K restorations will include Happy End (1978), Talented Donkey (1985), War on Our Streets (1989) by Gayane Martirosyan, The Congregation of Mice (1978), A Thousand and One Tricks (1981), Echo (1986) by Lyudmila Sahakyants, The Magic Rainbow (1979), Familiar Faces (1980), The Giant Who Dreamed of Playing the Violin (1986) by Elvira Avagyan and From the Life of the Little Trolls (2008), Ballet (2012) and Firdus (2020) by Naira Muradyan. The restoration of these films will not only help to expand perceptions of Armenia’s film heritage, but will also enrich our understanding of women’s contribution to world cinema.